Hah! I bet you thought I’d be posting about exclamation points! Exciting stuff! Focal points! But no, today I shall focus on the lowly, misunderstood, but oh-so invaluable comma. Let’s think for a moment about its role. According to Wikipedia, “the comma is used in many contexts and languages, principally for separating things.” So what exactly does that mean in terms of garden design?

Consider a journey through the garden. Is it a straightforward stroll or an oddyssey of sorts, a passage through a series of events large and small, past eye-catching vignettes and special moments? I prefer the latter. And to make that kind of garden, a place where one pauses to savor the moments, we need commas. They help structure a garden as surely as they do for a sentence. Just as a sentence can devolve into meaningless run-on gobbledy-gook without proper punctuation, so too can a garden. A grammatic comma tells you where to pause, and it separates long strings of words into meaningful clauses. A garden comma does the same thing–it divides a garden into structural episodes, or chapters.

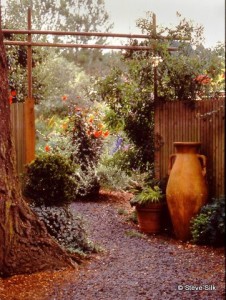

Now you can’t put a comma any old place. There are rules for its use in written language, but in the vernacular of the garden the rules, or rather guidelines, for its use are more subjective. First, what is a garden comma? It can be object or plant. But it’s not the thing itself that matters, it’s how and where it is used. It is NOT a focal point, those are more like exclamation points. A comma is more subtle. Its intent is to slow you down, to make a minor announcement, to get your attention, to say, “Here begins a new clause.” So, they are ideal for use at any transition point in a garden. Try some attention- getting but subordinate objet d’art or plant anywhere there’s a change in the garden. Let’s see how a few gardeners have used containers as commas: At a gate (above, in Jan Nickel’s Avon, Ct garden and at left in Ernie sand Marietta O’Byrne’s Eugene, OR garden), at the start of a path (below, Jan Nickel again-here the materials overhead and underfoot change as well, so this is a BIG comma), at the base of a set of stairs (top of the post). Those are some basic placements.

Now you can’t put a comma any old place. There are rules for its use in written language, but in the vernacular of the garden the rules, or rather guidelines, for its use are more subjective. First, what is a garden comma? It can be object or plant. But it’s not the thing itself that matters, it’s how and where it is used. It is NOT a focal point, those are more like exclamation points. A comma is more subtle. Its intent is to slow you down, to make a minor announcement, to get your attention, to say, “Here begins a new clause.” So, they are ideal for use at any transition point in a garden. Try some attention- getting but subordinate objet d’art or plant anywhere there’s a change in the garden. Let’s see how a few gardeners have used containers as commas: At a gate (above, in Jan Nickel’s Avon, Ct garden and at left in Ernie sand Marietta O’Byrne’s Eugene, OR garden), at the start of a path (below, Jan Nickel again-here the materials overhead and underfoot change as well, so this is a BIG comma), at the base of a set of stairs (top of the post). Those are some basic placements.

Pots aren’t the only thing that can serve as a comma, and points of transition aren’t the only place they can be used. More subtle placement draws attention not to a change, but to an immediate location. It says, “Hey, you’re in a special space, take a look around!” The neatly clipped boxwood balls in Bob Dash’s garden, Madoo, on Long Island, NY are just the thing to slow you down, to get your attention, and to make you aware of this particular “subordinate clause” within the overall garden.

Finally, its time to take a load off, sit down and perhaps contemplate the meaning and usage of commas in the garden. This bench in Wesley Rouse’s Southbury, CT garden gives us just the right opportunity. So often benches serve as a focal point or as a destination, so I particularly admire this placement, which is most definitely a comma. It’s NOT a destination, and its casual pathside setting is not a command; instead it is a gentle invitation to pass by, or to sit. Either way, it’s okay. Like the boxwood orbs, what it really says is, “Look around! You’re in a special little room in the garden. Enjoy!” Just like a comma, it offers a pause that refreshes.