When we go out into the garden to take pictures, we don’t always find what we expect. So don’t get locked into seeing what you want to see. See what is.

When my friend Kate Frey suggested I might want to photograph the tapestries of winter vegetables she planted at Lynmar Winery I could hardly wait for the next free morning. I knew her keen sense of design and plant combinations would be exquisite. An organic edible garden designed to be an artistic visual treat ?! Think the Roadrunner cartoons… zeeeeeeeeoooooooowwwwwwwwwwwwwww …. I’m on my way.

Pre-dawn in winter is cold, even in Northern California. Now, I say “cold” advisedly. I know we have readers in New England, the upper Midwest, even into Canada where the 30 degree morning I am calling cold would be called balmy. But when I rose in the pre-dawn morning of the shoot it was also foggy, a very cold fog. It became a very hard frost by dawn when I arrived at Lynmar.

At first I was completely disappointed. The garden was a frozen wilt; no life, no color, crunchy underfoot. I couldn’t take pictures of what I expected, I was only finding frost. “Work with what you’ve got” I told myself. See what is.

As I looked at the frozen leaves I realized I was given a wonderful opportunity. Rarely is frost so heavy, freezing fog is uncommon and the leaves were covered with crystals. Macro photography was in order.

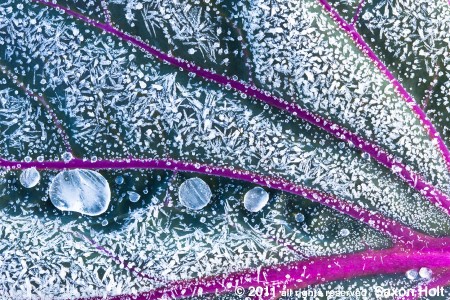

For these leaf studies, the most important technical factor was lining up the camera and lens to be as straight on to the leaf as I could manage. The plane of the camera and its digital sensor need to be as close to parallel to the subject as possible. This gives for the greatest depth of field.

Close-up macro work allows little of depth of field, it’s a simple optical function. To get the most depth possible the photographer needs a slow shutter speed, small aperture, and a tripod. For really close work one can never have everything in sharpest focus. The photographer must decide how to compose to take advantage of or mitigate parts of the frame that may be blurry.

These two chard leaves are not tack sharp throughout but the frost crystals in the center are razor sharp. The colorful sensuous midrib in each gives a bold design, so whatever may be blurry is not detracting from the composition.

I became a cold contortionist with my tripod that morning, trying to find a place to splay out my tripod legs so they did not land on (and thus break) a leaf, yet have my camera in just the right angle to fill the frame with leaf patterns and frost crystals. I could not always get as close to the plants as I would like, so I planned another “trick” – cropping.

Filling the camera frame from edge to edge with meaningful components to your photograph and for telling your story is a fundamental tenet of good composition. No wasted space in art.

The photos we imagine when we study a scene do not necessarily fit into the predefined shape of our camera sensor. Don’t feel constrained by what the camera frame shows you, cropping a photo is easy later in the computer. Have a plan and previsualize what your final photo will look like.

All of these leaf photos have been cropped at least a little so that the patterns fill the frame, but I had some fun with this next one.

It is actually a very small section of a larger photo, but I really wanted to see the frost crystals close up.

I like the larger photo too, but knowing my camera takes huge files I knew I could crop like crazy and still get a photo that looks clean – on a blog. It would never do in print, as the cropped photo is only 600 pixels wide (450 on the blog page). The original is 3373 pixels which would print as a 12 x18 print without interpolation.

The super cropped close-up allowed me to show a picture that was much tighter than I could have taken that morning even with my macro lens. I could not get any closer physically, so I simply planned on cropping later.

What I couldn’t catch on film as I worked that frosty morning was the glory of the sun waking the plants. As the sun warmed the cells, the plants literally woke up. I was startled at first by the subtle shakes and trembles I saw in the plants that windless morning. Then I realized I was witnessing private stirrings that only were noticeable on careful observation.

I wish I had planned for some time lapse photography, though I felt a little voyeuristic. The moment in the sun was so special, so small, so fleeting it could not have been captured.

But the sun began to warm me too. My own blood cells warmed up and I could feel my fingers again. As streaks of early light found their way into the garden it allowed for new thinking on what to photograph. No longer finding frost, I found the light. Photograph what is.