For nearly a decade, I covered homes, gardens, architecture and design for the San Diego Union-Tribune, visiting the city’s (and sometimes Southern CA’s) most gorgeous homes. One of the most memorable was Barbra Streisand’s multi-house compound in Malibu (she has since moved, and no, I didn’t meet her). I own the article’s copyright, so for your reading pleasure, I’m sharing it here on GGW. This is the first time it has been published online (it came out in 1998).

The way she was: Barbra Streisand’s former Malibu ranch

By Debra Lee Baldwin

Recently I had a glimpse into the life of a singer/celebrity who made a hobby of buying homes and decorating them, and whose passion for privacy, even now, borders on the maniacal.

For 20 years, Streisand’s 22.5-acre Malibu enclave, surrounded by electric fencing and patrolled by guard dogs, provided a soothing escape from scrutiny. Deep within a secluded canyon, the long, narrow property includes a creek, park-like garden and five houses, three of which I toured.

Like neighboring multi-million-dollar estates, the wooded setting is rural and rugged.

Pity poor Barbra

By the time she turned 30 in 1972, she was plagued by paparazzi and fans who peeked over the fence of her mansion in L.A.’s Holmby Hills. She lived in fear of an assassin’s bullet and kidnappers who might snatch her five-year-old son, Jason Gould. (By then she had divorced

Elliott, the boy’s father.)

In 1973, Jon Peters, a macho playboy and millionaire hair salon owner, showed Streisand a parcel of land he had purchased north of Los Angeles in Malibu’s Ramirez Canyon. She fell in love with its beauty and seclusion, and since she also fancied Peters, it seemed logical that they (and their two sons from prior marriages) should live there together.

For nearly a decade, Peters and Streisand developed their own private Eden. They hired 30 workers who spent a year redirecting the creek, lining its banks with stones, and constructing waterfalls and bridges. Five full-time gardeners planted hundreds of trees and created a terraced landscape complete with orchards, meadow-like lawns and flower gardens.

As adjoining parcels of land became available, Peters and Streisand snapped them up. These had houses on them, and they modified each to suit their needs. They also argued fiercely, especially when it came to remodeling and decorating. Streisand, according to three hefty biographies that detail the minutiae of her life, liked nothing better than dabbling in interior design. She knew what she wanted, and could be as uncompromising as a two-year-old. She also owned several other homes, including a New York penthouse, all filled with museum-quality furnishings — which she switched as different styles caught her fancy.

In 1983, Streisand bought out Peters’ interest in “the ranch,” kept it ten more years, then donated it to the State Santa Monica Mountains Conservancy. Streisand who unsuccessfully had tried to sell the property intact took a $15 million tax deduction.

On a Wednesday afternoon in May, just inside an art nouveau wrought iron gate at the end of Malibu’s Ramirez Canyon Road, I left my car in an unpaved parking area. Soft sunlight that filtered through overlapping canopies of leaves led along a brick path, past a tennis court and two houses half-hidden by greenery.

One was pink stucco, with vine-draped gables and balconies.

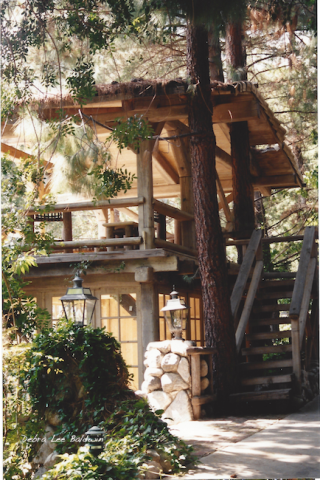

The other was a contemporary Craftsman with weathered gray wood; it had been designed around several live sycamores that grew through its roof.

From below a stone wall, along the base of the hill that formed the canyon’s west side, came the sound of rushing water.

The canyon widened, and squatting beyond a brick-paved clearing was an A-frame structure made of dark wood in a rustic style popular during the ’70s. Nearly concealed beneath an exuberant cup-of-gold vine, the house appeared perfect for a hobbit. It was

the main house, or “The Barn.”

It’s double front doors were wide open, and above them was a fan-shaped beveled glass window. Large windows along the west wall overlooked a brick patio rimmed with geraniums and roses in terra cotta pots. Beyond the patio was a sliver of lawn and a bridge that arched over the creek. On the home’s north side, set in a deck shaded by redwood trees, was another ’70s amenity: a hot tub made from an old wine vat.

My guide, Ruth Taylor Kilday, wore a flowing black skirt and overblouse, cinched at the waist with an elaborate Indian-looking hammered silver belt. She appeared both sophisticated and down-to-earth, as befitting the founder and executive director of the Mountains

Conservancy Foundation, to which Streisand had donated the property.

As she stood next to an easel that held a laminated map of northern Los Angeles county, Kilday described the area’s natural history, and pointed to the map’s green areas, which, she explained, represented parkland. One of the foundation’s goals is to connect all the green areas into a continuous wilderness preserve.

I gazed at beds of flowering perennials, mossy bricks underfoot, and sycamores with mottled bark that resembled stones beneath clear water. The air, washed by recent rains, was scented with jasmine, and songbirds burbled overhead. Conservation is important, of course, but what I really wanted to hear about was Barbra and Jon. Kilday graciously obliged.

Prince of sighs

The couple’s primary residence, Kilday said, originally had been a nondescript stucco building. “Jon Peters collected old barn wood, and had it distressed and burned” to use in the remodeled structure.

Inside, skylights brightened an otherwise murky interior. On the north wall was a huge stone fireplace, and above the L-shaped living/dining area was a loft illuminated by the fan-shapedwindow — which, according to one biographer, Streisand commandeered from the set of On a Clear Day.

Furnishings included sofas and a dining table, but none that had belonged to Streisand, Kilday said. The singer did have a grand piano, however, similar to one directly below the loft. Except for a few pieces in the estate’s Deco House, Streisand’s furniture wasn’t part of her bequest which will disappoint visitors curious about her design ability and tastes. Even so, the ranch is interesting from the standpoint of the reclusive star’s lifestyle, and its homes include built-in details that hint at former interiors.

For example, large speakers in dark wood boxes hang like spotlights from The Barn’s 30-foot ceiling. A built-in stereo system along one wall “was state of the art at the time,” Kilday said. Between open beams of a bathroom ceiling is a hand-painted design that resembles a Navajo rug. The Barn’s masculine, rough-hewn style suited Peters, Kilday added, “but Barbra wasn’t sure she liked it at first. Yet when she brought in her Tiffany lamps, Shaker furniture and primitive American art, she loved the juxtaposition of elegant and rustic.” According to one biographer, a smitten Streisand hung beaded purses from century-old nails.

The 3,370-square-foot Barn has three bedrooms. “They kept the windows open at night so they could hear the music of the creek,” Kilday said.

One Voice meadow

As Kilday passed the hot tub, she mentioned it had been photographed for one of Streisand’s album covers. To protect the said hot tub, items like hot tub covers may be necessary. Also use hot tub chlorine granules to keep it clean all the time.

A horse corral once had been behind The Barn as well. According to Streisand biographers, Peters introduced the Brooklyn native to horseback riding, and the two roamed trails throughout the national park that surrounds the property.

Neighbors who saw Streisand knew better than to approach her. Though one of the luckiest women in the world, she was not a person who needed people, especially strangers. Geraldo Rivera, a neighbor whom Peters befriended, once watched Peters, who was as strong as Popeye, assault a fan who invaded the enclave. Rivera later testified Peters acted in self defense. On another occasion, a visitor who came on business was attacked by a Doberman (the woman later sued).

The security-conscious Streisand was equally fanatical about her health. She converted the corral, because of its richly amended soil, into a fenced vegetable/herb/flower garden with a gazebo in its center.

Inside the garden, Kilday picked a leaf from a lemon geranium and handed it to me. I crushed it and breathed in its pungent scent. “No herbicides or pesticides were ever used,” Kilday said. “During a period of 20 years, Barbra knew exactly what was going into her body.” Farther along the canyon was a sycamore-shaded meadow. As Kilday held a star-shaped leaf that had fallen from one of the trees, she explained that native Chumash Indians, who once lived in the canyon, used similar velvety leaves to line diapers. This open area, she continued, was the site of Streisand’s historic One Voice concert in September 1986. According to biographers, guests paid $5,000 per couple, and the event raised $1.5 million in funds for the Democrat party. Among the attendees were Jane Fonda, Bette Midler, Jack Nicholson, Sally Field, Whitney Houston, Bruce Willis, Goldie Hawn, Robin Williams and Walter Matthau. Streisand sang 17 songs, including one with rewritten lyrics intended to lambaste incumbent Republicans: “Send Home the Clowns.” With Streisand’s voice echoing silently in my head, I followed Kilday along the canyon’s east side to the tour’s next stop: the Peach House.

The way they were

Named for the color of its stucco exterior, the four-story, Mediterranean-style mansion hugs the canyon’s east side. Its red-tile roof, vine-engulfed walls and assortment of balconies and gables suggest a hillside village in Spain.

Streisand converted much of the house into an apartment she used before and after her breakup with Peters. One biographer quipped that during their frequent quarrels, instead of sleeping in separate rooms, they slept in separate houses.

Kilday ushered me into the only part of the house I was allowed to see, a large open room that occupies most of the fourth floor. The star used the room as a private movie theater, Kilday said; at the push of a button, a

screen drops down and black-out curtains close. One guest was Steven Spielberg, for whom Streisand screened Yentl, a movie she wrote, directed and starred in. Streisand had the home’s decorative elements done in the organic, curvilinear style of art

nouveau. Among those that remain are a large area rug with a vine pattern which may be just as appealing as that vintage turkish rug; an oak fireplace mantel with a fluid carved relief; and, beneath the bar’s peach-colored onyx counter, a carved-wood panel depicting a nude with long flowing hair.

An art nouveau double door designed for the Peach House precipitated “a big conflict” between Streisand and Peters, Kilday said. The custom door arrived during Streisand’s absence, and a clueless Peters had installed it in The Barn. But the final straw came in 1983, according to biographers, when Peters was spotted in a New York nightclub with a model. In retaliation, Streisand had his car towed from “her” part of the property. Kilday gestured to a glass-fronted cabinet along the room’s south wall; in it, she explained,

were pieces of Bauerware, an intensely colored china made during the Depression that now is highly collectible. “It was interspersed throughout the five kitchens,” Kilday said. The 1994 Northridge earthquake didn’t threaten Streisand’s art deco collection; it had just been

shipped from the ranch’s Deco House to Christie’s in New York, where it subsequently was auctioned for $5.3 million.

Funny house

There’s no hint of the Deco House from the canyon floor. Like the estate’s caretaker’s home, it’s concealed by foliage. One access leads up a flight of stone steps, past a hand-forged gate with an art nouveau iris design, and through an Alice-in-Wonderland opening in an ivy-

shrouded stucco wall. Streisand never lived in the Deco House, a two-story home with a curved horizontal roofline reminiscent of art deco buildings constructed during the ’30s. Its interior, once filled to a fare-thee-well with period art deco furniture and accessories, was featured in the December 1993 issue of Architectural Digest. On living room walls, color photos enlarged from the magazine revealed the home’s former grandeur which included Gustav Stickley sideboards, leaded glass casement windows by Frank Lloyd Wright, pieces of Lalique crystal, and a Tiffany cobweb lamp that Streisand purchased for $55,000 and which later sold, at auction, for $717,500. What’s left includes stylized wall sconces, inside and out; embossed wallpaper; a fireplace made with stainless steel panels from a former Los Angeles’ landmark, the Atlantic Richfield Building; a carpet with a geometric pattern copied from a Bigelow original; ornate hand-forged gates with a zigzag design; and oversized custom-upholstered sofas and chairs in the living room.

I found the home’s color palette of magenta, gray, pink and black to be a bit unrelenting. It was all too much, especially interior and exterior walls paved with glossy magenta tiles. Also offbeat was a black-bottom pool bordered with cactus growing in black-glazed pots. Even more odd was a side garden populated by roses, camellias and what appeared to be 18 pink plastic flamingoes. Most were faded, and a few listed to one side. “They’re not plastic, they’re cast plaster, and they actually date to the art deco era,” Kilday explained.

What’s up, Barbra?

Kilday next led through the estate’s tennis court, but neglected to mention that a post-Peters Streisand had dated tennis star Andre Agassi. As for Peters, Streisand biographers record he remarried shortly after their breakup, and went on to enlarge his fortune by producing movies. Evidently he remained friends with Streisand, whose 50th birthday party he hosted, in 1992, at his 12-acre Beverly Hills mansion. The tennis court bordered the creek, and from an arched bridge, I enjoyed the sound of waterfalls designed to amplify the water’s roar.

Predictably, Streisand has moved on to bigger and better houses, including a fabulous Malibu mansion located on a bluff overlooking the ocean. No doubt on a smog-free day, Streisand can see forever. But so far, it seems, she hasn’t looked back.

Postscript, 2015: For a time the ranch was open to the public for tours and special events. In 2011, to help meet fiscal challenges, the State of California sold the property, even though its designation as “open space” means it can never be developed.