Written by Jill Sinclair

Alot of GGW readers already know Jill from her popular blog, Landscape Lover, where she gives her personal take on parks and gardens in Paris and further afield. Jill is a British landscape historian, trained in the US and London, and currently living in Paris. Her particular interest is the changing meaning and value of historic places. In 2009, the MIT Press published her first book, Fresh Pond, which explored the shifting significance of a site in Massachusetts. She also contributes regularly to a range of peer-reviewed journals and popular websites, and gives lectures and guided tours on the history and associations of particular landscapes. I’m a big fan of Jill and Landscape Lover….if you haven’t yet read it, check it out. Fran Sorin

What makes a garden Japanese?

When asked by a client to design her a Japanese garden, landscape architect James Rose replied: “Sure – whereabouts in Japan?”

Yet many gardens around the world are confidently described as Japanese. Indeed, James Rose’s own home and gardens at Ridgewood in New Jersey, which I visited a few years ago, were clearly influenced by his great love of Japanese gardens, even though he baulked at anyone describing them as such.

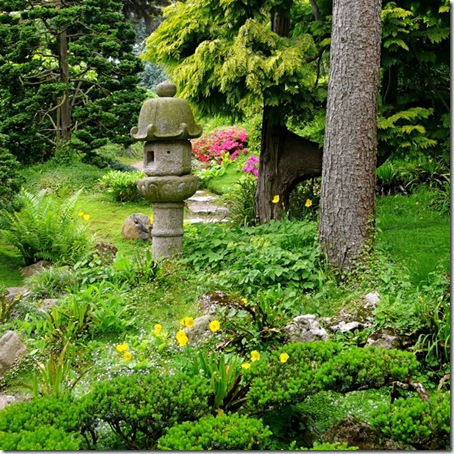

Here in Paris we have several beautiful sites which are known as Japanese gardens. Just to the west of the city are the wonderful grounds of the musée Albert Kahn. Originally created by a French banker and philanthropist in the early twentieth century, the museum’s surroundings include a traditional Japanese garden, with lanterns, temples, a tea house, carefully placed rocks and clipped shrubs, all explored on winding stone paths.

In 1989 part of it was replaced by a contemporary Japanese garden, created by landscape architect Fumiaki Takano, who is known for his work on children’s playgrounds and parks. The contemporary garden is easily the most popular part of the museum’s grounds, especially at this time of year when flowering is at its peak. Every day it is full of visitors enjoying the water features, Japanese plants (azaleas, maples, irises, willows, rodgersias, pines), the pathways and stepping stones, the textured pebbles, the red painted bridges; indeed all the features that people in the West associate with Japanese gardens.

Yet one expert on Japanese art has told me that he dislikes the new garden, believing it has too much concrete to be authentic, and that he preferred the slightly disheveled traditional garden that was there before. Another scholar has rather dismissively described the new garden as a “confection.”

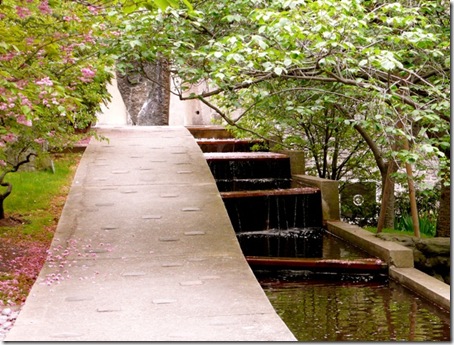

A second Japanese-style garden can be found in Paris at the UNESCO headquarters. The peace garden (jardin de la paix) was designed in the late 1950s by the Japanese-American sculptor Isamu Noguchi. It contains features commonly associated with Japanese gardens, such as cherry blossom, pools and streams, stone bridges and sculptures, and a place for tea ceremonies. But Noguchi also deliberately introduced more Western elements, including contoured surfaces, extensive amounts of concrete, a stage or viewing platform that allows visitors to see the whole garden at one time, and a design that bears the strong personal imprint of its creator.

This mixture of Eastern tradition and Western modernism led to complaints that the garden was too showy (to Japanese eyes) or conversely too austere (for Europeans). Some denounced it as almost a caricature of Japanese style: American sculptor Alexander Calder famously refused to have one of his works placed within the peace garden for fear that Noguchi “would probably cover the base with powdered sugar and call it Fujiyama.” Yet today such criticisms are to a large extent forgotten, and Noguchi’s design is widely accepted as an iconic example of a Japanese stroll garden.

At a time when our sympathies remain with those suffering the effects of the recent earthquake in Japan, gardeners’ thoughts readily turn to the enormous influence that the country has had on Western design. And yet how far do we in the West really appreciate the subtleties and symbolism of Japanese gardens? Are we too ready to describe a patch of raked gravel and a stone lantern as Japanese? On the other hand, can a garden in the West perhaps count as Japanese if it was designed by someone with links to Japan (as were the two Paris examples)? Or was James Rose right that the location is all that matters – if it’s not in Japan, it’s not a Japanese garden?